By Ryan Schwab

The establishment of no mow areas on golf courses is gaining popularity. In Minnesota, fine fescues are typically the species chosen due to their low-input characteristics. Fine fescues grow slowly, and they generally have low nutrient and water requirements, all of which saves golf course resources. They also may provide the desirable aesthetics of a waving pasture with gold-frosted seed heads, which is quite the contrast from the well-manicured playing surfaces of fairways and greens (Figure 1).

A lot of thought and planning goes into installing no mow areas to keep them from disrupting play. Unmown fine fescues can become thick and tall, which makes playing a ball in them difficult. This is why they tend to be established in out-of-play areas on a golf course. The location of a no mow stand will factor into other decisions such as fine fescue density and weed thresholds. The seeding rate will determine fine fescue stand density, which may further influence other factors, such as weed encroachment or seed head number. At the University of Minnesota, we’ve demonstrated that hard fescue seeded between 1.8 and 5.5 lbs/1000 ft2 provides acceptable stands with low weed counts. These seeding rates create hard fescue stands that may differ from some no mow areas found in our region that appear similar to space plantings with very low plant densities. Our goal was to combat weeds by installing a no mow fine fescue dense enough to crowd out weeds at establishment and eliminate the need for herbicides. The space plantings approach may help golfers spot their balls quickly, but weed pressure is usually high.

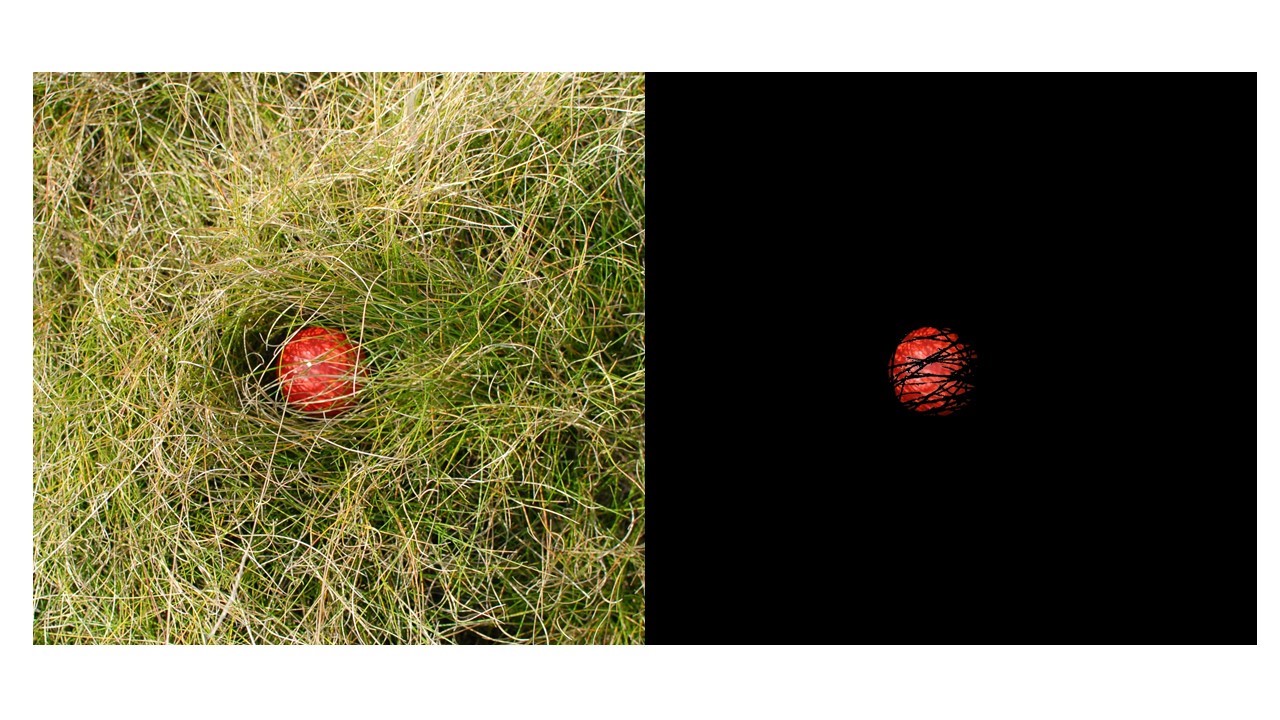

Spotting a golf ball, let alone playing it, in no mow areas can be challenging. One goal of our research on hard fescue no mow roughs was to evaluate the visibility of a golf ball tossed in plots seeded at three rates (1.8, 3.7, and 5.5 lbs/1000 ft2) with four different mowing regimes (mowed at 4” in the spring, fall, spring & fall, or not mowed at all). Red golf balls were tossed into each plot and digital images were taken from overhead at a set height. An image analysis pipeline (Heineck et al., 2019) was then able to determine how visible each golf ball was by identifying red pixels of the ball (Figure 2). Golf ball lie was variable, as some balls rested on top of the hard fescue, while others hid under a thistle canopy or vole tunnel.

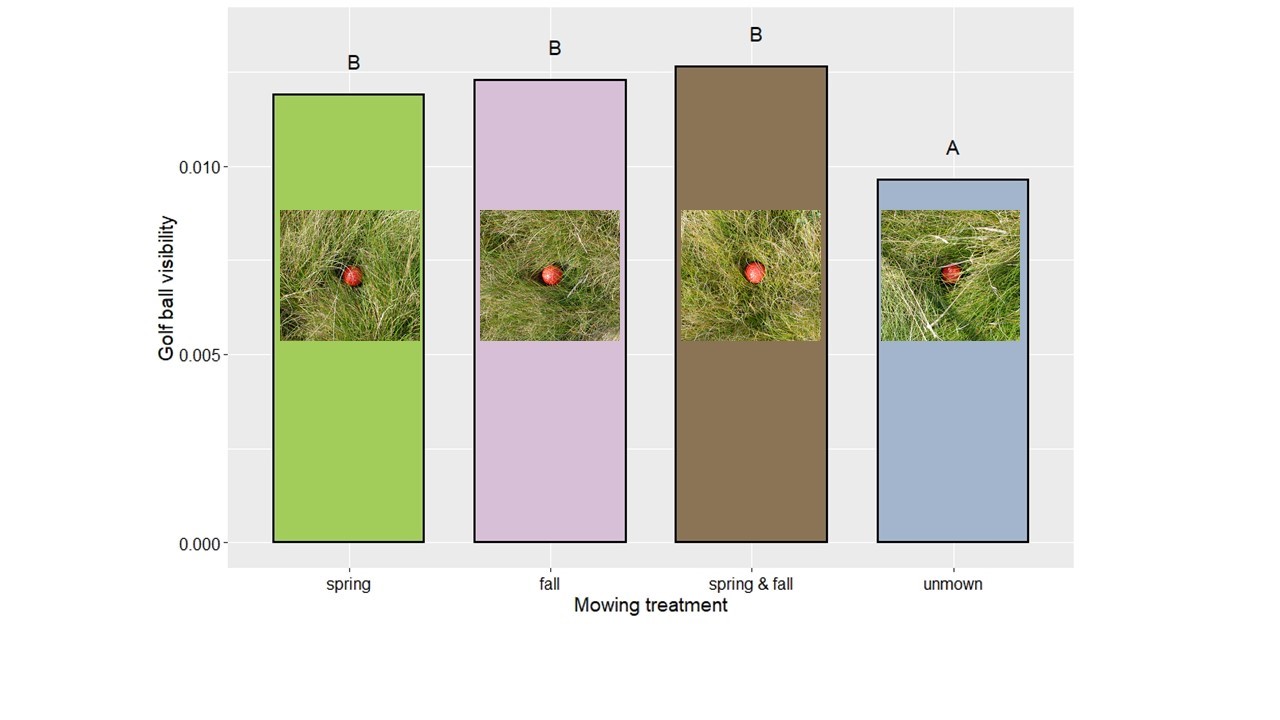

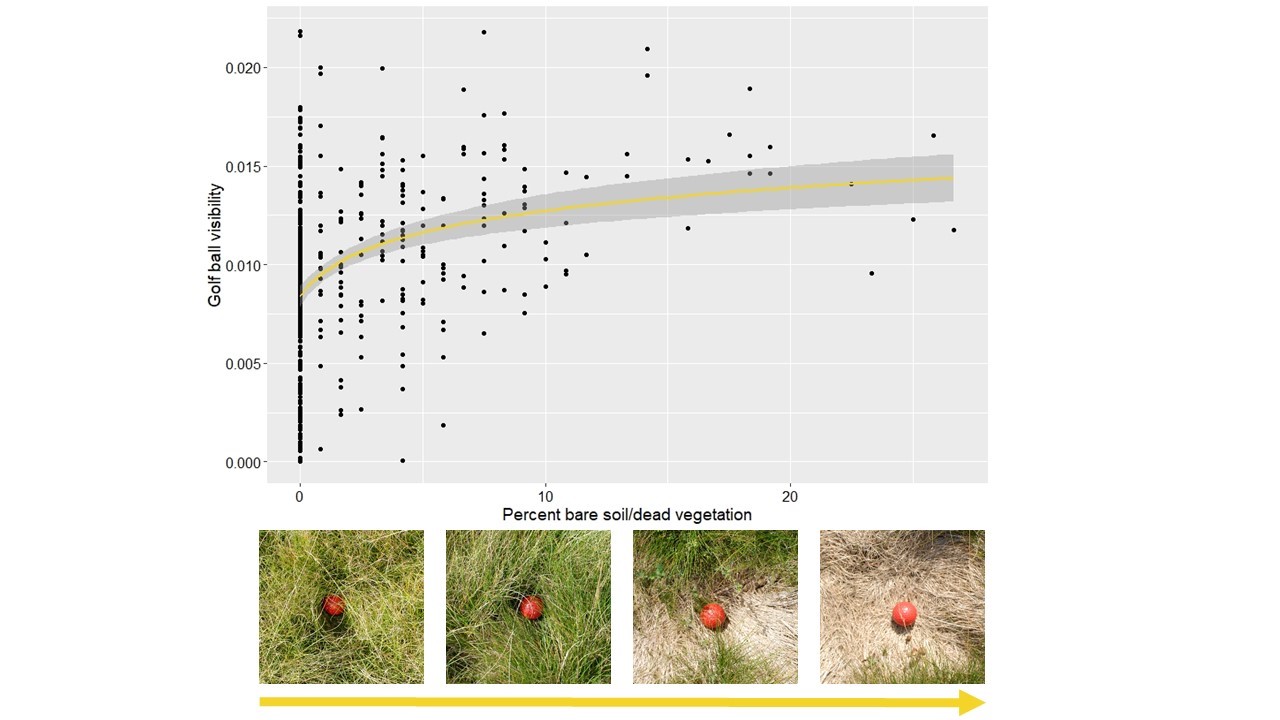

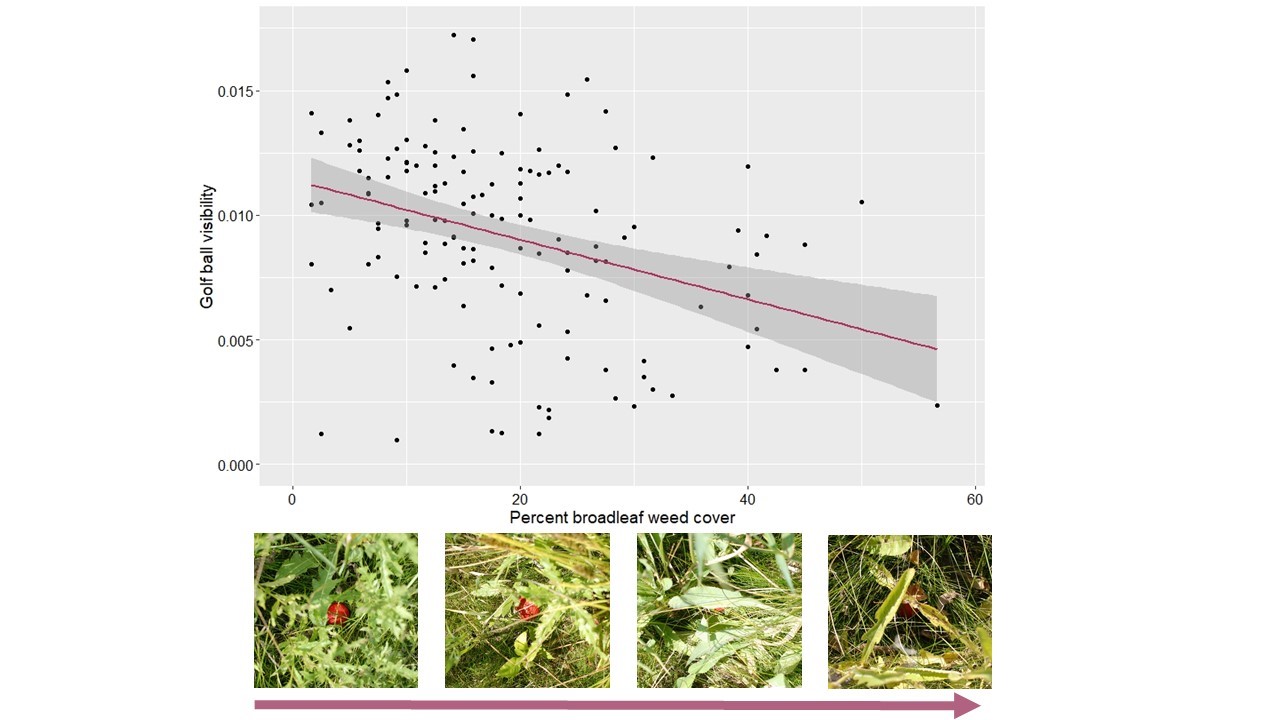

Despite the variability, we’ve made simple conclusions about which factors may influence the visibility of a golf ball in no mow roughs. In the first year of mowing treatments, we noted that golf balls tossed in the unmown plots were less visible than those that were mowed (Figure 3). Although significant, the visual difference to the human eye is slight. A portion of our plots had pockets of dead hard fescue or bare soil. Golf balls became more visible in plots that exhibited these dead pockets (P < 0.001; r = 0.37; Figure 4). At one research location, there was a lot of weed pressure, and results from this location indicated that as broadleaf weed cover increased, golf ball visibility decreased (P < 001; r = 0.34; Figure 5). Dense thistle canopies made it challenging to spot golf balls.

Golf ball visibility is a complicated element of no mow roughs. Not only can factors such as mowing regime, density, and weed pressure influence a ball’s lie, but there’s already a lot of variability involved in the trajectory of a golf ball shot. Our results indicate that management of no mow fine fescues is important in areas where golf ball visibility is desired.

We would like to thank the United States Golf Association, the Minnesota Golf Course Superintendents Association, and Rush Creek Golf Club for supporting this research.

Reference

Heineck, G. C., I. G. McNish, J. M. Junger, E. Gilbert, & E. Watkins. (2019). Using R-based image analysis to quantify rusts on perennial ryegrass. The Plant Phenome Journal, 2, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.2135/tppj2018.12.0010 [Open Access]